Poem Of The Week: Death and Old Age with Shakespeare

Not sure if it is the almost-bare trees outside the window or the dying embers of the warm winter fire in the fireplace that reminded me today of one of my favorite poems to teach. William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, usually known as “[That Time of Year Thou Mayst In Me Behold],” has been a go-to poem for me for years. (You can find a ready-to-go lesson plan on this poem by clicking here.)

It’s a typical Shakespeare sonnet in many ways: an older man talks about himself and the love that his beloved feels for him; there’s lots of beautiful imagery; the speaker wrestles with a problem and comes to something of a solution in the end.

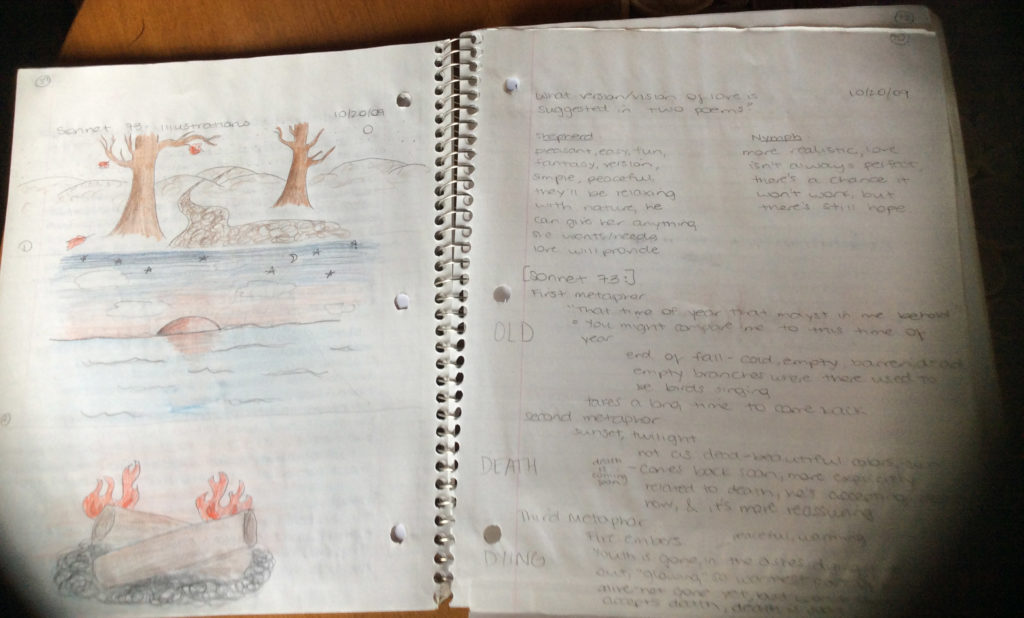

By working through three different metaphors to describe the way it feels to love someone who will be dead soon–a bare tree, a setting sun, and the dying embers of a fire–the speaker comes to the conclusion that sometimes things that will be gone soon are even sweeter for their fleetingness. I do love this idea, and it’s a great one to introduce Romeo And Juliet–yes, they bug the heck out of me with their stupid violence and teenage ways, but what is there in literature more beautiful than their few minutes together as husband and wife?

Okay, I’ll admit that old age and death is not always an easy sell with teenagers. But I think that this is an important poem to teach because from what I’ve seen in our society, death is almost always seen as a terrible thing to avoid at all costs. We talk about fighting and pushing on and longevity… but there is something beautiful about death, especially when we see it as a natural part of life. And although I don’t get into the concept to deeply with my classes, I like them to know that there isn’t only one answer, ever.

“[That Time of Year…]” is pretty versatile. I have taught it as a whole-class discussion, and I have assigned students to work through it with partners or groups. I have taught it as an introduction to Shakespeare before a play unit or as a part of a small unit on figurative language. I have also taught it as part of a chronological British Lit unit.

Yet no matter how I teach it, I always have students draw the three images of the poem. There is something about drawing those images that helps them really understand the subtleties of the language. (The trees in the first part don’t have birds in them anymore–they once did but not now. It isn’t a fire at the end but the glowing embers, etc.) I also love to give visual learners a chance to work through poetry on their own terms whenever possible–and this poem is a great choice for that.

When you get this kind of art from regular ole’ classwork, you know it’s worth it.

And since it so easily transfers to a drawn image, it’s a great choice for teaching with interactive notebooks.

This is the kind of poem that I refer back to throughout the year. When I am teaching my AP students to analyze poetry, I always tell them that once they have found the general theme statement, they should look for ways that the speaker is conflicted. A poem usually ends on some kind of resolution, though it is not always an entirely satisfying one. This poem is a great example of that.

I also like the reminder that while one day I too will die, for now, those bare trees outside will eventually grow buds and leaves again, and the dying fire can be restarted with some fresh new logs, and maybe when I do die, it won’t be so bad after all.

Want to teach this poem with a ready-to-go handout that gets students thinking about the big ideas by analyzing the imagery and language? Click here to check out my lesson plan for this poem.